Venice, Italy

Tim Cooke

It’s the biggest and most international art show on the planet! An estimated 500,000 curious art lovers will visit the 57th Venice Biennale between May and November this year. More than 80 nations are taking part in the official exhibitions, creating a kind of blend of an Olympics and United Nations of the art world.

The main focus is at two sites – the Giardini Della Biennale where 30 countries have their permanent “pavilions” and the Arsenale, where the vast caverns of this former naval shipyard have been transformed into a visual arts extravaganza – a maze of colour, shape, form and media.

Art-lovers gather at the Giardini

The Arsenale hosts dozens of installations

A host of other countries offer exhibitions and installations scattered around the city in churches, palazzi and other venues, while dozens of commercial galleries also use the occasion to promote their favoured artists on a global stage.

While each nation (and its representative artist) does its own thing, there is an overall attempt to create a broad theme. This year French curator Christine Marcel has created the theme “Viva Arte Viva”, a statement I suppose that art has its own intrinsic worth and relevance in a world which currently seems riven with uncertainty.

Among the highlights is Phyllida Barlow with Folly at the British Pavilion. Outside the Pavilion, unnoticed by the stream of visitors, I encountered the artist herself, somewhat endearingly bemused by all the publicity her work is generating. At the age of 73, Phyllida is attracting more attention than ever. Rightly so, as she has much to share. As Nick Serota said at the opening, her works squeeze the space and fill the visitor’s consciousness with their volume and presence.

Phyllida Barlow outside the British Pavilion

Folly inside the British Pavilion

Big crowds too for the U.S. Pavilion, where Mark Bradford’s work in the age of Trump is a talking point. The artist has established a reputation for exploring themes such as the vulnerability of marginalised people and unfulfilled social promise. Bradford says this work is not a direct response to President Trump, rather that as an artist he has been “mining this territory” for a long time.

The Venice exhibition Tomorrow Is Another Day moves to Baltimore after the Biennale ends

Visitors encountering Mark Bradford’s work inside the U.S. Pavilion

Detail from one of Mark Bradford’s works inside the United States Pavilion.

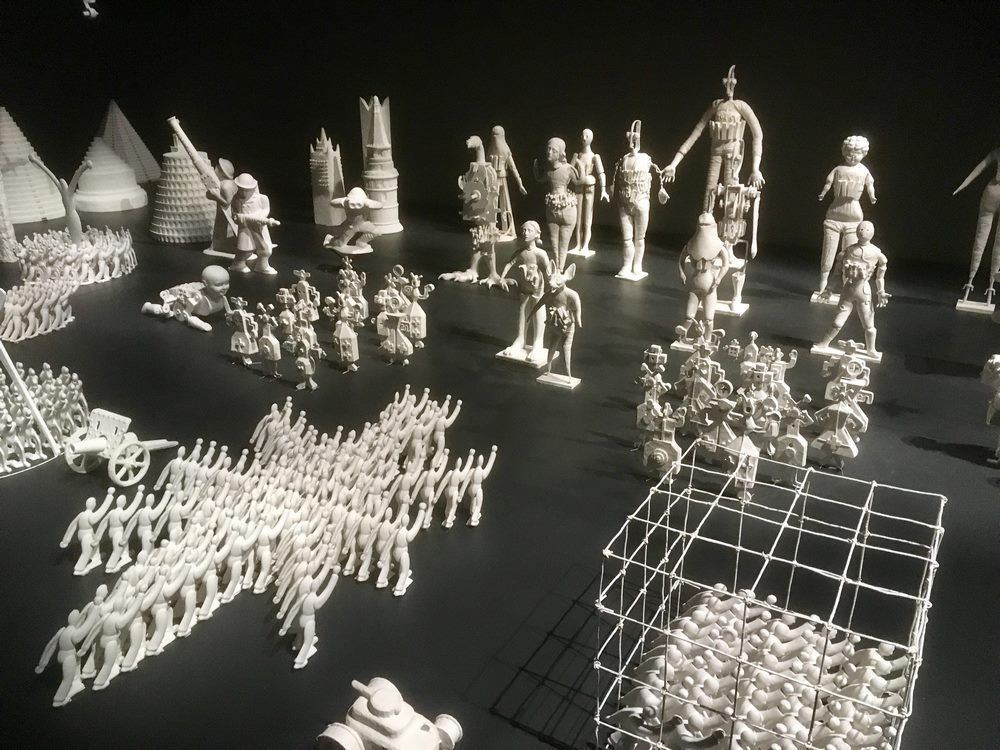

The Russian exhibition grabbed my interest. Entitled Theatrum Orbis (Theatre of the World), it features work by Grisha Bruskin and Sasha Pirogova.

Scene Change inside the Russian Pavilion

The Canadian installation is accessible and refreshing. If you go to visit, you’ll see what I mean.

Away from the Giardini and Arsenale it’s also worth the short vaporetto ride out to Isola di San Giorgio – you’ll be rewarded with a lovely view back across the water towards San Marco and will see three quite different exhibitions featuring engaging work by the leading 20th-century Italian artist Alighiero Boetti, Michelangelo Pistoletto’s mirror installation in the Basilica di San Giorgio Maggiore and virtual reality commissions by Paul McCarthy and Christian Lemmerz.

Among the commercial galleries selling their wares in a Venice this season is London-based Victoria Miro. The gallery used the occasion to launch a new Venice enterprise. The opening show ‘Poolside Magic’ features watercolours by Chris Ofili. There are many other commercial shows catering for all kinds of tastes.

Venice is of course a wonderful city to visit for many reasons and the 57th Biennale offers even more justification for a trip this year for those who want to explore some of the latest trends in contemporary art around the world. The Biennale runs until November 26, 2017.

Separate from the official Biennale is a whole other enterprise which has been attracting headlines and dividing critics – Damien Hirst’s new show Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable. The clue is in the title. A spoof story about sunken treasures allegedly recovered from the deep. The show is in two venues – the Palazzo Grassi and the Punta della Dogana – and it doesn’t matter which you visit first.

A diver purportedly salvaging one of Damien Hirst’s “treasures”

Hirst and his backers have spend a lot of time and money coming up with this one and it’s really quite a spectacle. It’s billed as Hirst’s “most ambitious and complex project to date”. Audacity abounds. But some critics ask if it is really art? I’m not sure that’s the question. It is what it is and doesn’t pretend to be anything other.

The artist is playing wildly here – with his imagination, with Venice and with art aficionados. He is playing too with questions of authenticity, credibility, gullibility, juxtaposition, objectivity, subjectivity, longevity, cultural consumerism – and collecting itself. No accident at all that this is in Venice and that it coincides with the Biennale.

A “treasure” in the Palazzo Grassi

Does this “treasure” remind you of anyone?

One of the galleries in the Punta della Dogana

Some aspects of it are clever, some less so. As an experience it is certainly worth a visit. Is there a strong sense of art history in the making? For me, not really. But the scale and range of this venture are such that I’m sure it will be talked about for years to come.

The show runs in Venice until December 3, 2017.