Dublin, Ireland

Tim Cooke

Sean Scully (b.1945)

Window One, 2014

Private Collection

© Sean Scully

Photographer: Robert Bean

This year he’s so international there almost may not be enough countries to keep up with Sean Scully. When I caught up with him in Dublin – city of his birth – at the start of his show in the National Gallery of Ireland, Sean was fresh off a plane from Barcelona, where he’d been fresh off a plane from the Venice Biennale.

All this after triumphant exhibitions this year in Shanghai and Beijing, and active or forthcoming shows in Brazil, Austria, Germany, France and Spain. Nothing, I guess, to a man who lives in three places (near Munich, in New York and in Barcelona) and who derives fresh verve and raw connectivity from his constant movement.

And this is in fact the point. His painting is a global and living language that keeps updating itself, its forms and themes finding resonance beyond borders and cultures.

This is exactly why, in 2010 as Director of the newly-refurbished Ulster Museum in Belfast, I went with my curator colleague Anne Stewart to see him at his Bavarian studio to invite him to come to Belfast and lead the re-opening of the museum after three years of closure and major refit.

His exhibition then was beyond anything ever seen in Belfast before. After decades of violent conflict evolving into a shaky peace, the major cultural space in the city was rejuvenated with 83 works boldly proclaiming their themes of illumination, negotiation, resolution – and the warmth and joy of human possibility.

“One might say,” Sean wrote to me at the time, “that Art is the opposite of war. In my work the subject of light is omnipresent…. light in our history, being deeply associated with illumination and the unique human quality of being able to imagine a flexible future.”

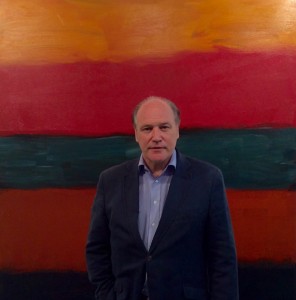

Tim Cooke with Sean Scully’s Landline Red Red (2014). courtesy Kerlin Gallery, Dublin

It is a message to which many are receptive. The language of art transcends borders and the stereotypes so often imposed on everyone from our close neighbours to peoples on the far side of the world.

Dublin has always been a generous city and one to which Sean constantly returns. His work has played a prominent role in recent years in the Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane under its visionary Director Barbara Dawson but it is fitting that Sean Scully is being accorded the honour of being the first living artist to have a major solo show in the National Gallery of Ireland just across the River Liffey.

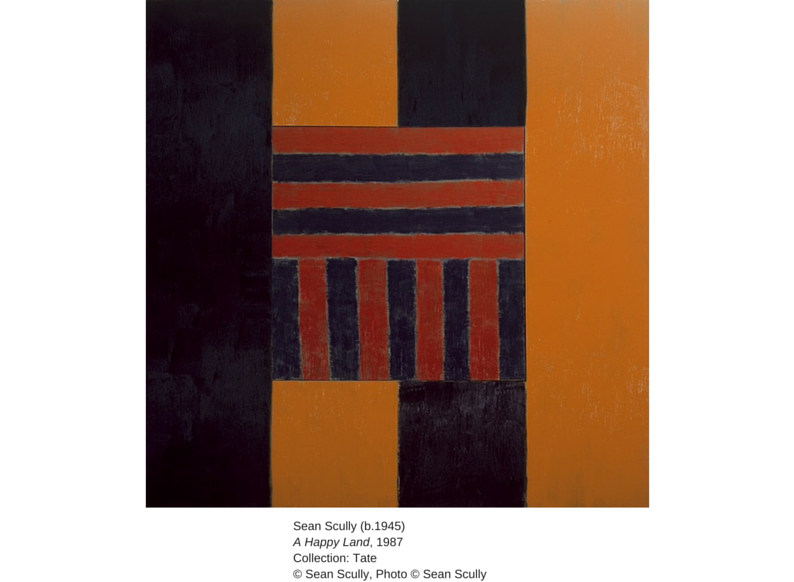

Although there are only fourteen works on display, the exhibition feels larger. It fills the first floor gallery suite in the Millennium Wing and includes works with multiple iterations, for example photographs from the Aran series of 2005 and a series of C-prints Manhattan Shut made last year. Major works from his oeuvre include Paul (1984) which commemorates the death of the artist’s son and A Happy Land (1987), both on loan from Tate.

The exhibition, which runs until September 20, 2015, has been curated by the Gallery Director Sean Rainbird. The catalogue includes an essay by the critic Kelly Grovier.

Tim Cooke with Sean Scully and Sean Rainbird, Director, National Gallery of Ireland

While chatting with Sean in Dublin recently, he spoke with his own unique blend of honesty and immodesty of the “phenomenon” of how his work was received this year in China, saying that he couldn’t understand it and was still trying to come to terms with it.

But the heart of the answer is simply this. He certainly does understand how to use paint to illuminate and give voice to the inner parts of the human spirit as they seek to interpret the encounter of the individual with the changing traffic of global life today. And his work offers solidarity to individuals and societies exploring the interplay of the certainties and uncertainties of identity and diversity, of self and other, as we live together in an increasingly crowded world.

* * * * *

The Sean Scully exhibition at the National Gallery of Ireland in Dublin runs until September 20, 2015. See nationalgallery.ie

The Kerlin Gallery in Dublin is staging a selling exhibition of Sean Scully’s work entitled Home until August 29, 2015. See kerlingallery.com

Dublin City Gallery The Hugh Lane has a permanent exhibition of Sean Scully’s work. See www.hughlane.ie