Zonnebeke, Belgium

Tim Cooke

With events marking the centenary of the Battle of Passchendaele now attracting global interest (the battle ran from July 31 to November 10, 1917) the Belgian museum dedicated to exploring the conflict is attracting more attention than ever.

Despite the overwhelming bleakness of the narrative they must tell, there are some very thoughtfully-conceived museums on the Western Front, adding to an arresting array of memorials, cemeteries and commemorative events.

The Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917 at Zonnebeke to the east of Ypres is one such museum. It merits a visit if ever you have the opportunity and are prepared to have both your reason and your emotions led into uncomfortable territory.

Weapons on display at Zonnebeke

The exhibitions and the replica trench network leave you in no doubt about the unimaginable extremity of the harshness of this battle in which some 500,000 men died, went missing or suffered unimaginable injuries in the space of 100 days.

Much has been written about the muddiness and bloodiness of the terrain and the battle. You are struck in this museum by the horror of the conditions, the relatively crude and destructive nature of the weaponry, the way in which mules and horses were so appallingly mis-used, the inhumanity writ large on every level. And this, remember, was only ten decades ago.

You can smell chemically-simulated mustard and chlorine gas. You acquire a sense of the industrial scale of the battle as you survey the display cases filled with helmets, weapons, artillery shells, uniforms and gas masks. You are also given a sense of the international impact of the conflict with sections explaining the role of troops from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, Ireland and Great Britain. And in an unusual design twist, artillery shells have been displayed in an artistic manner, creating a colourful and reflective installation.

An unusual display of artillery shells

Individual panels explore the role of different nations in the battle

The museum is housed in Zonnebeke Chateau, a somewhat unusual building on the site of an older chateau which was (like pretty much everything else in the region) destroyed in battle. The parkland setting is deceptively pastoral, with a fishing lake and walkways.

The Dugout Experience in which visitors can walk a series of replica tunnels and trenches is designed to create a sense of how and where soldiers spent their time, although the conditions are inevitably sanitised compared to the historical reality.

Passchendaele was part of the infamous Ypres Salient and the area is layered with opportunities to explore First World War history.

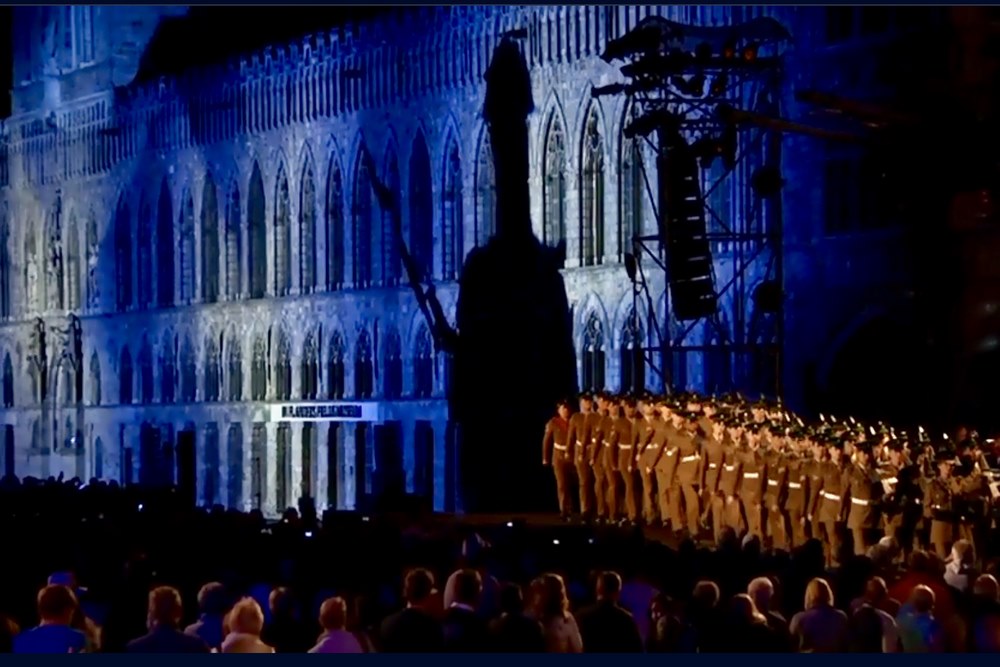

In Ypres itself, which witnessed such shocking destruction, you will find the In Flanders Field Museum in the rebuilt Cloth Hall. It offers real insight into both the strategic issues at stake all across the Western Front – and their appalling human consequences. The use of interactive technology, holograms and video here is excellent and effective. It was the Cloth Hall building which was used as the backdrop in the July 2017 televised centenary tribute to those who were killed at Passchendaele.

The Passchendaele centenary event at the Cloth Hall, Ypres

A visit to the nightly ceremony at the Menin Gate in Ypres (where the official centenary commemoration took place involving The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge and the King and Queen of Belgium) is a revealing reminder of the global nature of the conflict as pilgrims make their way from the far corners of the world to join in remembrance and reflection.

Crowds gather for the nightly ceremony at Menin Gate

To the west of Ypres lies Lijssenthoek Military Cemetery with its thoughtfully-designed Visitor Centre opened in 2012. This also is a thought-provoking visit. One of the features of the Visitor Centre is its focus on telling the personal stories of the men who lie buried here. Another feature is the effective use of interactive maps to explain the changing battlefield.

The Visitor Centre at Lijssenthoek

Inside the Visitor Centre at Lijssenthoek

Interactive maps allow visitors to explore the changing battlefield

In Lijssenthoek I also witnessed the care that still goes into maintaining these cemeteries today with meticulous re-etching of the stonework which so distinctively marks the graves.

Etching the gravestones at Lijssenthoek

Whatever the reasons behind a conflict, suffering is of course never one-sided. Langemark, a cemetery for the German dead, is the final resting place for 44,294 soldiers. It may seem to be stating the obvious in relation to a cemetery but if you visit you may see what I mean when I say that I was struck by the subdued, restrained character of Langemark.

Langemark German Military Cemetery

To visit the Western Front is to make a commitment to exploring a past which is terrible in the extreme. But it’s a commitment I would recommend. To see the places where battles were fought, to explore why they came about and how they unfolded, to experience the physicality of the terrain and to witness even now the consequences of such a destructive conflict is an experience of profound and enduring value.

Not far from Ypres and close to the Memorial Museum Passchendaele lies the largest Commonwealth War Graves cemetery in the world, Tyne Cot, with 12,000 graves. Its visible scale is such that you will be be compelled to both feel your breath… and catch it.

One hundred years on from this constantly shocking period of human history, the dead of Passchendaele still speak.

Tyne Cot cemetery