New York

By Tim Cooke

If you’re in New York and heading for the 9/11 Memorial Museum on the site where the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center stood, prepare yourself for a tough visit.

Part of the Comms Aerial from the Twin Towers

Inside the museum your mind and emotions will be assaulted with a sense of the force, shock and human horror which unfolded when the two planes were steered into each of the towers, resulting in the deaths of some 3,000 people.

It was an event with a global and ideological context and impact, although most of the focus of the museum is on what happened to the victims, the subsequent rescue effort and the ensuing impact on New York City.

The anguish experienced by the victims and their families is uncompromisingly portrayed in the main exhibition galleries, with video, audio, individual stories and personal effects. The visitor is inevitably drawn into the trauma inflicted on New York in September 2001. Its intensity is hard to step back from. The emphasis of the interpretation is on experience, emotion and memory.

Tim Cooke at the 9/11 Memorial Museum in New York

There’s a different quality of experience to be found in the large, quieter spaces which form part of the memorial complex. There are three voluminous areas which offer a context for thought and personal reflection.

Firstly the vast outdoor cathedral, created by the two vacant one-acre footprints of each of the Twin Towers, amidst a Memorial Plaza. Here, the sounds of the constantly pouring waterfalls mingle with the ambient noise of downtown Manhattan.

The Memorial Hall

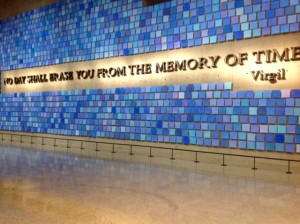

Secondly, inside the museum, the large wall which encloses a repository containing the human remains of many victims. Blue squares represent those who died. A quote from Virgil, in letters forged from metal recovered from the wreckage, reads: NO DAY SHALL ERASE YOU FROM THE MEMORY OF TIME.

Thirdly, in the cavernous subterranean main hall, the exposed foundation wall of one of the towers where the last metal column to be removed from the wreckage stands like a totem pole, creating a scene evocative of a modern-day Carthage, urging the inner self to contemplation on the progress – or otherwise – of human civilisation.

In its first year of operation, 2.7 million people have visited the museum. Some 19 million have visited the Memorial Plaza.

The Main Hall at the 9/11 Museum

As a memorial and a museum to such a cataclysmic event this project is trying to do many difficult things at once. At one end it plays heart-rending recordings of the final calls from victims to loved-ones. At the other it attempts to mark the scale and significance of events which continue to shape the course of global history.

It’s trying to do these things relatively close in time to the terrible events it marks – always a massive and complex task when feelings are so raw, when anger remains prevalent, when consequential wars are still being fought.

In relation to 9/11, knowledge, understanding and reflection are goals to be pursued by visitors and non-visitors alike, whether in New York or around the world. History cannot, of course, be changed. It can and should be remembered. But its future course depends, as always, on the attitudes and choices of those of us privileged with the gift of life today.