New York

By Tim Cooke

Dramatic headlines in the art world as both a single painting and a single sculpture soar to world record auction prices in New York.

Giacometti’s L’homme au doigt sold for $130 million

© The Estate of Alberto Giacommetti. Courtesy Christies

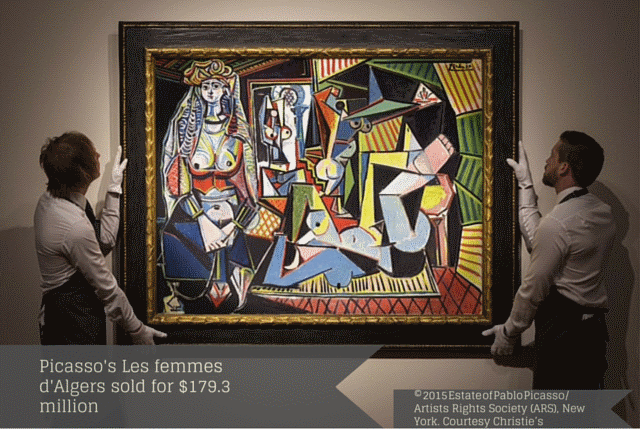

Pablo Picasso’s oil on canvas Les Femmes d’Algers (The Women of Algiers) made $179.3 million at Christies ( £115 million) while Alberto Giacometti’s life-size bronze L’homme au doigt (Pointing Man) made $141.3 million (£90 million)

The Picasso is the highest price ever for a painting sold at public auction. The previous record was for Francis Bacon’s triptych Three Studies of Lucien Freud which made $142 million in 2013.

Les femmes d’Algers (Version “O”) is the fifteenth version in a series and was painted in 1955.

At the same auction Alberto Giacometti’s L’homme au doigt, a bronze sculpture from an edition of six conceived in 1947, made a record-shattering $141 million. The previous auction record was also for a work by Giacommetti. L’homme qui march I (Walking Man I) sold for almost $104 million in 2010.

Overall, the top levels of the art market have continued to soar in recent years. So, what does any of this tell us and what is the relationship between art, money and meaning? What is it that drives individual collectors, corporations and top museums to pay such high prices for works of art?

At this level, investment is a major reason. The vendor of this Picasso made a tidy profit, having bought the painting for $31.9 million in 1997. In the case of this and similar paintings, the importance of the artist, his/her place in the history of art, where the particular work sits in the artist’s oeuvre, the rarity and provenance of the piece, will all have worked their way into the price.

However, buying art in order to make a profit can be a precarious enterprise. It’s not for the faint-hearted. Most advisors will suggest you buy a painting because you like or even love it – and want to live with it for years. If it increases in value over time then so much the better.

Sometimes collectors are attracted to pieces which capture a sense of their identity, their own history or their sense of place. Or they might have an empathy with works which portray a mood, represent a particular artistic movement or reflect an intellectual or existential concept.

A major work may also have a timeless quality to it. This can be powerfully appealing to the human race, with individuals being so limited by a human lifespan. A work of art can take on a sense of destiny as part of the story of human civilisation. It may also reflect or inspire a sense of something beyond ourselves, something fundamental, universal, transcendent.

Museums and major galleries like works which are crowd-pullers for sure, although most of the great ones have more quality works than they can handle already.

Whatever the reason, these are amazing prices. However, not many of us can afford them. I am among those fortunate to have various pieces of art hanging on my walls – none of them, I hasten to add, anywhere close to this level of value. But they hold some meaning for me. Some of them are landscapes reflecting my own sense of place, some capture moments of human experience and social history to which I feel a connection, some touch my consciousness with their colour and sense of joy.

I hope the new owners of the Les femmes d’Algers and L’homme au doigt enjoy their pieces as much as I enjoy mine, irrespective of their monetary value. And, well, if they really want to swap…