Ypres, Belgium and Thiepval, France

Tim Cooke

The scale of the conflict is perhaps beyond the comprehension of any individual – so too the enduring impact which 100 years on still draws visitors from across the globe to the battlefields, memorials, cemeteries and museums of the Western Front.

It was in the fields of Flanders in Belgium and of northern France that some of the worst carnage in human history unfolded during World War One (1914-1918). Today, in both regions, more visitors than ever are getting close to this terrible history by visiting battle sites and the many, many cemeteries which lace the countryside.

The largest Commonwealth cemetery – Tyne Cot near Zonnebeke in Belgium – is the burial place of almost 12,000 soldiers, 8,000 of them unidentified. Tyne Cot is a place of such scale that, paradoxically, it subdues your eye and spirit. A visual survey of the gravestones tightens the jaw and makes your mouth go dry. Any sense of logic is jolted and displaced. You struggle to find emotional balance. Your mind and spirit rebel and protest against the uncompromising truth of the sight before you.

Tyne Cot Cemetery in Flanders, Belgium

It’s remarkable too to witness the nightly ceremony at the Menin Gate in Ypres, where visitors from all over the world gather at 8pm for a ceremony of remembrance. It’s moving that such a ceremony continues with such consistently large and international attendance.

Nightly ceremony, Menin Gate, Ypres, Belgium

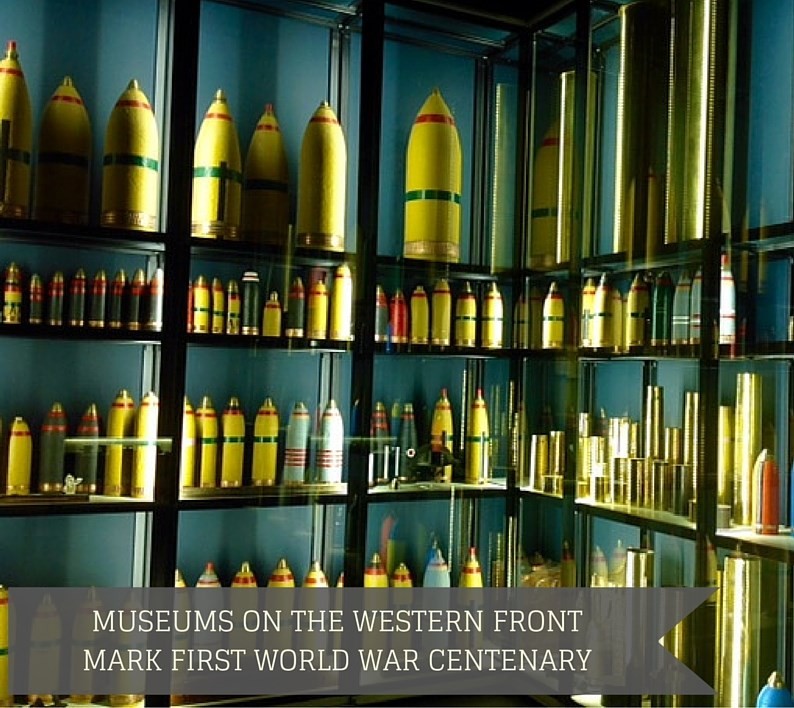

Flanders is a place where memorialisation is evident all around, including in the powerful In Flanders Fields Museum in the centre of Ypres, where modern design and interpretation techniques are employed to tell the story of the Western Front. The museum is situated in the rebuilt Cloth Hall which was itself destroyed during the war. The museum was recently refurbished and expanded to re-open in July 2012 in preparation for the centenary. It is a thoughtful and well-conceived museum with skilful use of imagery, objects and interactives.

In Flanders Fields Museum, Ypres, Belgium

So too the nearby Memorial Museum Passchendaele 1917, which opened in July 2013, with its recreated trenches and arresting narrative. A visit here is another memorable and impactful engagement with the past, leaving a lasting impression of the scale and depth of horror of this battle.

Trenches, Memorial Museum Passchendaele, Belgium

Farther south in Picardy, northern France, this year – 2016 – marks the centenary of the Battle of the Somme. Here in the Somme countryside you encounter an astonishing contrast with the notion of such terrible carnage. The landscape today is beautiful, the setting for the cemeteries and memorials so tranquil.

One hundred years ago this summer my grandfather was on this battlefield. He was to survive the Battle of the Somme which claimed the lives so many of his young friends across the summer and autumn of 1916. In a later battle he suffered a shrapnel wound which led to his medical discharge and return to his home city of Belfast. At the age of 26 he had witnessed horrors about which he was never able or willing to speak for the rest of his days.

His was a small story in a much larger narrative which was was to shape the face of Europe and the lives of hundreds of millions across subsequent decades.

My grandfather returned home from the Western Front to an Ireland which was itself convulsed with change and which was locked into a cycle of events which was to shape the rest of his life and the lives of subsequent generations. Thus it is with great events, with tumultuous conflicts which warp and colour our experience of the world and which inevitably shape our outlook on our own lives and times.

The Ulster Tower at Thiepval Wood is the memorial to the 36th Ulster Division which fought with such loss at the Somme in July 1916. It is modelled on Helen’s Tower on the Clandeboye Estate outside Belfast where soldiers from the 36th Ulster Division trained before leaving for the Front.

The Ulster Tower at the Somme, northern France

The nearby Thiepval Memorial to the Missing, designed by Sir Edward Lutyens, stands 43 metres high and dominates the surrounding countryside. With its 72,000 names it is truly monumental in scale and import.

Thiepval Memorial to the Missing, Somme, northern France

An enduring memory of my visit to the vast expanse of earth around the Somme region today is the immediate and ever-present sound of skylarks overhead. These birds on the wing are the now distant relatives of those same larks who oversaw battle on a massive scale, when the sky around them burst with shells and shattered light on a terrifying scale.

The poetry of the First World War, piercing and profound, holds an arresting place in the pantheon of human verse. It was the English soldier-poet Isaac Rosenberg, who while serving on the Western Front, so poignantly captured the sound of the larks in this poem…

Returning, We Hear Larks

Sombre the night is.

And though we have our lives, we know

What sinister threat lurks there.

Dragging these anguished limbs, we only know

This poison-blasted track opens on our camp –

On a little safe sleep.

But hark! joy – joy – strange joy.

Lo! heights of night ringing with unseen larks.

Music showering our upturned list’ning faces.

Death could drop from the dark

As easily as song –

But song only dropped,

Like a blind man’s dreams on the sand

By dangerous tides,

Like a girl’s dark hair for she dreams no ruin lies there,

Or her kisses where a serpent hides.

This poem was written in 1917. On April 1st, 1918, Private Rosenberg was killed at dawn after returning from a night patrol.