Mostar, Bosnia

Tim Cooke

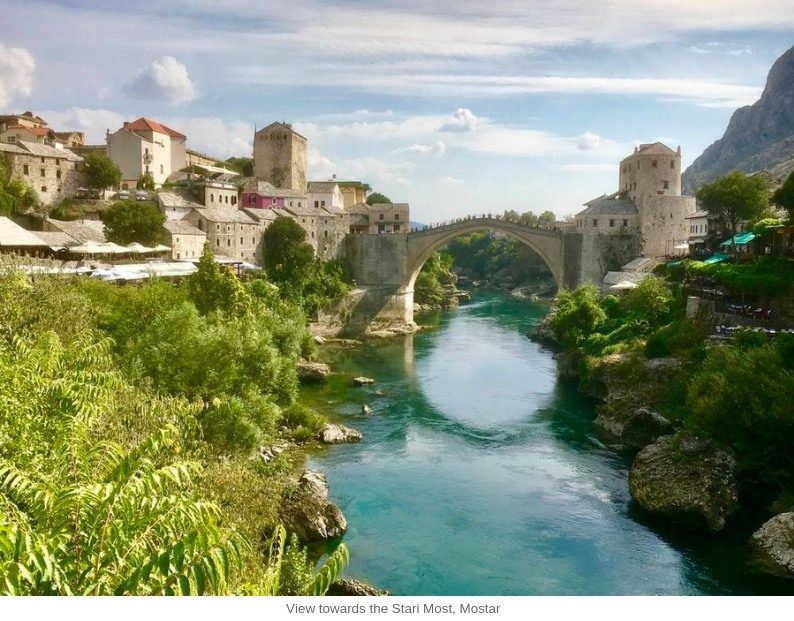

From atop the minaret of the Koshki Mehmed Pasha Mosque by the Neretva River you get a commanding view over Mostar, a city infamous during the brutal civil war in the former Yugoslavia in the early 1990s when its battered bridge linking the Croat side of the city with the Bosniak side finally collapsed under deliberate and sustained bombardment.

Stari Most or Old Bridge, Mostar

The sight of the bridge tumbling into the waters of the river below in November 1993 became an enduring image of the terrible conflict which tore Bosnia apart. This was a bridge with serious history – commissioned in the days of the Ottoman Empire by Suleiman the Magnificent. It stood for 427 years before the impact of dozens of shells fired by Croat forces created a visible and symbolic gap between the peoples of this city. This was an attack that was less about strategic infrastructure and more about the visible and uncompromising demolition and removal of a cultural symbol which had traversed centuries – a pattern repeated time and again across the Balkans during this terrifying period of conflict.

The coincidence of religion, ethnic identity and cultural history is so often a powerfully destructive and frightening force when it finds its way into an unleashing of widespread and uncontrolled violence. The destruction in the city was widespread. Some 2000 citizens died.

The war and its consequences changed the make-up of Mostar’s population, with Bosnian Serbs largely deserting the city and today the split is roughly half and half Bosniak Muslim and Croat Catholic.

In the case of the destruction of the Stari Most, the international community was to respond with vigour and imagination in devising a project to rebuild the bridge and the links across this city between people who found themselves at war with their neighbours. When the war ended, an international committee was formed with the support of UNESCO, the World Bank, the Aga Khan Trust for Culture, the World Monuments Fund and a number of European governments.

The eventual reconstruction and reopening in 2004 became equally powerful symbols of the efforts to rebuild and reconnect both city and people. The rebuilding of the bridge was accompanied by urban conservation schemes and a variety of individual restoration projects.

For some reason this bridge has been present in my thinking for many years and the notion of crossing it has been on my bucket list for quite sometime. Although I’ve been through Mostar before in different circumstances I was always under time pressure and I’ve never had time to pay the bridge a visit. Now I’ve been able to put that right.

Today the bridge is a tourist attraction in its own right, drawing a million visitors a year.

A million visitors a year now cross Mostar’s Old Bridge

The hump-backed bridge itself stands 24 metres above the Neretva. Its 4 metre-wide polished stone surface is extremely slippery, very easy to slide around or fall on as you negotiate its 30 metre length. Halfway across you might be lucky enough to see one of the youths who make their living from the donations of tourists dive from the apex into the river below.

Visitors to Mostar today can expect a memorable and rich adventure in the old town. The food is spectacular and the Turkish coffee and Turkish Delight are worth half-an-hour of anybody’s time. In recent years the number of souvenir shops and restaurants has multiplied.

This is for one?

Old Town, Mostar

Old Town, Mostar

Old Town, Mostar

Among the mix of shops and cafes is a museum telling the story of the war – the Museum of War and Genocide Victims. Another museum – the Bosnaseum – in the Old Town’s main cobbled street is an unusual mixture of folk museum and war story. A seven-minute video documents the destruction and rebuilding of the bridge and there is an informative array of black and white photographs of damage inflicted on Mostar and its key buildings during the conflict.

Inside the Bosnaseum

Inside the Bosnaseum

The Minaret of the Koshki Mehmed Pasha mosque

Inside the Koshki Mehmed Pasha mosque

It’s always fascinating to see what people can achieve in and with a place which has endured such destruction and travail. It isn’t really that long ago that Mostar was synonymous with war, ethnic division and barbarity. To see it now thriving as a cultural and tourist destination in its own right and with its different religious and cultural sites so accessible is a cause for hope.

Nevertheless the peace in the Balkans – whether in Mostar, Sarajevo or Kosovo – is in many ways an unsatisfactory peace. Deep divisions along ethnic lines remain, running through territory, education, sport, entertainment, local services and of course through religion and politics – all prone to exploitation and perpetuation.

But progress is progress and Mostar remains a case study for both local and international cooperation in re-imagining what is possible in the aftermath of the most tragic and seemingly hopeless human experiences. Hopefully, in the future, it can do even more.