Oxford, England

Tim Cooke

If ever for a moment you’re tempted to imagine that the quality of the collection isn’t absolutely at the heart of a great museum then take yourself to the city of Oxford and immerse yourself for a day in the unending delights of its great university museums.

These are museums with collections to drool over.

The Ashmolean Museum surveys most of the world’s great civilisations with galleries dedicated to the Aegean World, Ancient Egypt, China pre and post AD 800, European Prehistory, India pre and post AD 600, Islamic Middle East, Japan 1600-1850, Rome, Baroque Art and Chinese Paintings among others.

In one gallery you will find acres of porcelain. In another Stradivari’s famous violin The Messiah hangs amongst other important instruments and tapestries. Another gallery hosts the Great Bookcase by William Burges – said to be the most important example of Victorian painted furniture ever made. There is a Money Gallery. Such variety.

The Ashmolean: acres of porcelain

Detail from the Great Bookcase by William Burges

An encounter with the Ashmolean’s collections offers range and beauty. You get a strong sense of a collection underpinned by knowledge and scholarship. You are struck afresh by objects as emblems of civilisations, as illustrations of great craftsmanship, as embodiments of human history.

The current summer exhibition at the Ashmolean – Raphael: The Drawings – is a lovely show and draws heavily on the museum’s own collections. Much attention is focused on the final work in the exhibition, Study of the heads and hands of two Apostles c. 1519-20 from The Albertina in Vienna. I was drawn to The Virgin with the Pomegranate c. 1504 (also from Vienna) and the Studies for the Madonna of the Meadow c. 1505 from the Ashmolean collection.

Detail from Study for the heads and hands of two Apostles, courtesy Albertina, Vienna

Detail from The Virgin with the Pomegranate, courtesy Albertina, Vienna

If you can drag yourself away from the delights of the Ashmolean and take the 10-minute walk from Beaumont Street to Parks Road (or feel free to do it the other way around) then you are in for more museological magic.

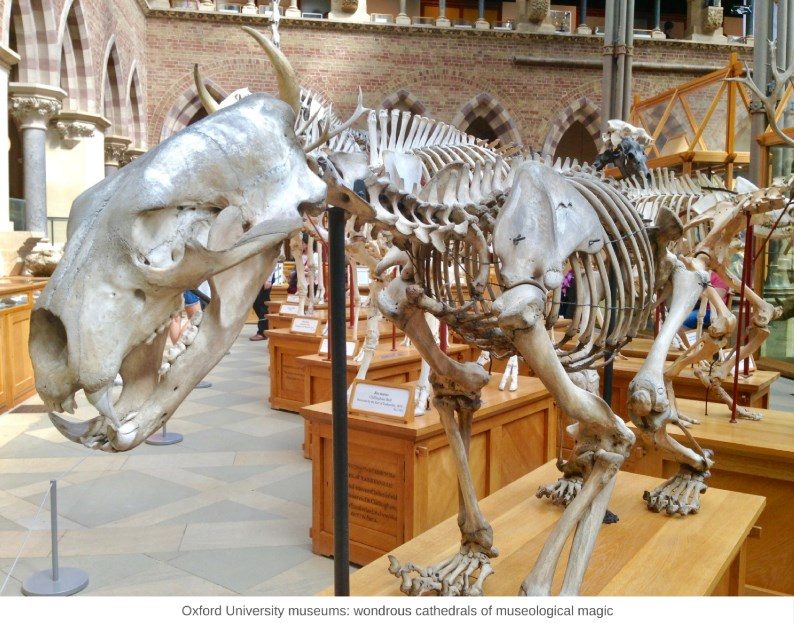

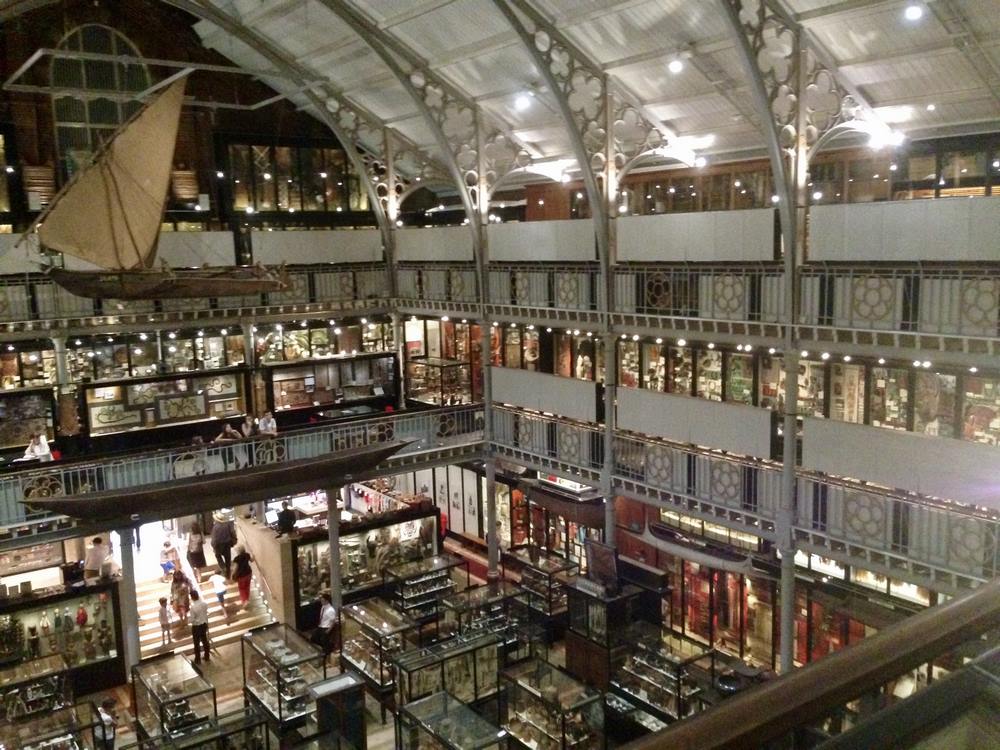

The Museum of Natural History and the Pitt Rivers Museum of Anthropology and World Archaeology (you walk from one directly into the other) are so astounding that they are almost unbelievable – veritable fantasy cathedrals of displays ranging from shrunken heads from the Upper Amazon to a sealskin canoe from the North West Passage.

The Museum of Natural History

Both museums are jam-packed (in a nice way) with displays which will have your mouth opening like a goldfish. Both are somewhat old-fashioned in lay-out and character – an absolute virtue in this case, running somewhat counter to prevailing trends for state-of-the-art interpretation. It’s the strength of their collections which make this possible. In many ways the objects, their combination and their context speak for themselves.

Inside the Pitt Rivers

The Museum of Natural History houses Oxford University’s zoology, entomology, palaeontology and mineral collections. The Pitt Rivers is a high-density experience which eschews the usual interpretative approach in ethnographic and archaeological museums of displaying the objects according to geographical or cultural areas. Here, instead, the exhibitions are arranged according to type – weapons or masks or textiles or tools, showing how common human challenges were addressed at different times by different peoples.

Moving on to the Museum of the History of Science in Broad Street you enter the original or Old Ashmolean Building which dates to 1683. Here you will find Einstein’s Blackboard, used when he gave his Oxford lectures in 1931. There is a wide range of scientific instruments including quadrants, astrolabes, sundials, telescopes, clocks and cameras.

The Museum of the History of Science

The museum is also home to the Marconi Collection, an unrivalled array of objects charting the evolution of wireless communication (the Marconi documents archive is housed nearby in the Bodleian Library).

From the Marconi Collection

It’s often the case that university museums are not among those best-known by the public. These museums – like many university museums I’ve visited – are an excellent demonstration of how scholarship, ambition, depth, range and quality stand the test of time and how they stand out powerfully in a museum landscape in which content, rightly, is still king.